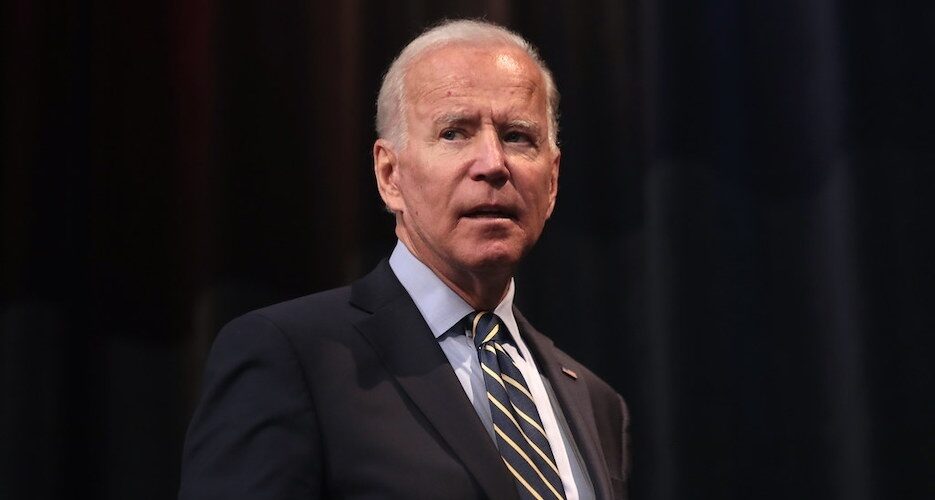

President Donald Trump’s approach to North Korea was defined by “tough” talk, threats and very little follow-through. It’s safe to say that many foreign policy analysts, particularly North Korea watchers, welcome a fresh start in January.

Biden’s previous executive branch experience was as part of an administration that was cautious – many would say to a fault – but this meant no preemptive military action, hollow summit declarations or deals that the U.S. couldn’t back out of if the North did not honor them.

President Donald Trump’s approach to North Korea was defined by “tough” talk, threats and very little follow-through. It’s safe to say that many foreign policy analysts, particularly North Korea watchers, welcome a fresh start in January.

Biden’s previous executive branch experience was as part of an administration that was cautious – many would say to a fault – but this meant no preemptive military action, hollow summit declarations or deals that the U.S. couldn’t back out of if the North did not honor them.

Try unlimited access

Only $1 for four weeks

-

Unlimited access to all of NK News: reporting, investigations, analysis

-

Year-one discount if you continue past $1 trial period

-

The NK News Daily Update, an email newsletter to keep you in the loop

-

Searchable archive of all content, photo galleries, special columns

-

Contact NK News reporters with tips or requests for reporting

Get unlimited access to all NK News content, including original reporting, investigations, and analyses by our team of DPRK experts.

Subscribe

now

All major cards accepted. No commitments – you can cancel any time.