About the Author

Nick Hall

Nick Hall is a writer based in Sydney, Australia. Follow him on Twitter.

Get behind the headlines

|

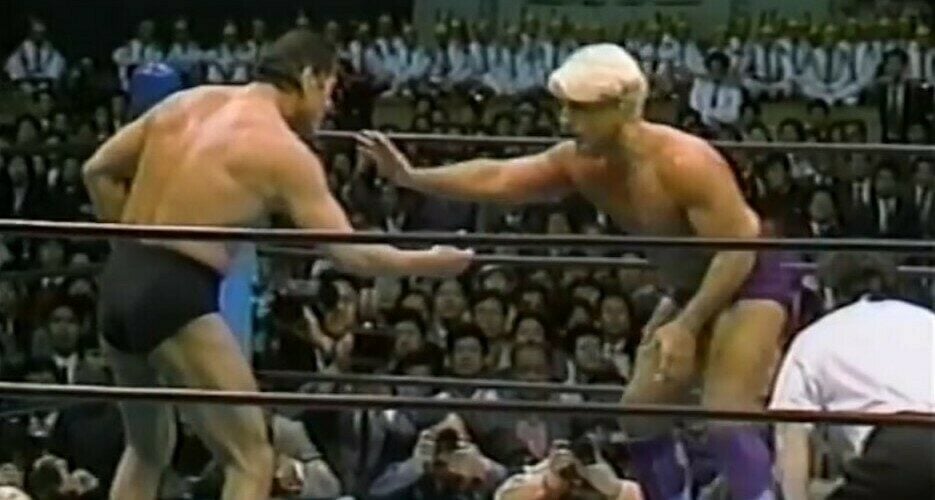

Evergreen Collision in Korea: Pyongyang’s historic socialism and spandex spectacular25 years ago, North Korea set a new world record for the largest pro wrestling attendance ever that still stands today  This week marks the 25th anniversary of one of sporting history’s most bizarre events, ‘Collision in Korea’ – North Korea’s curious foray into American professional wrestling, which remarkably still holds the record for the world’s largest pro wrestling attendance ever. Two decades before basketball star Dennis Rodman would make headlines with his attempts at ‘basketball diplomacy’ with North Korea, boxing legend Muhammad Ali led another sports diplomacy mission there to promote peace between the country and its adversaries, the United States and Japan. © Korea Risk Group. All rights reserved. |