|

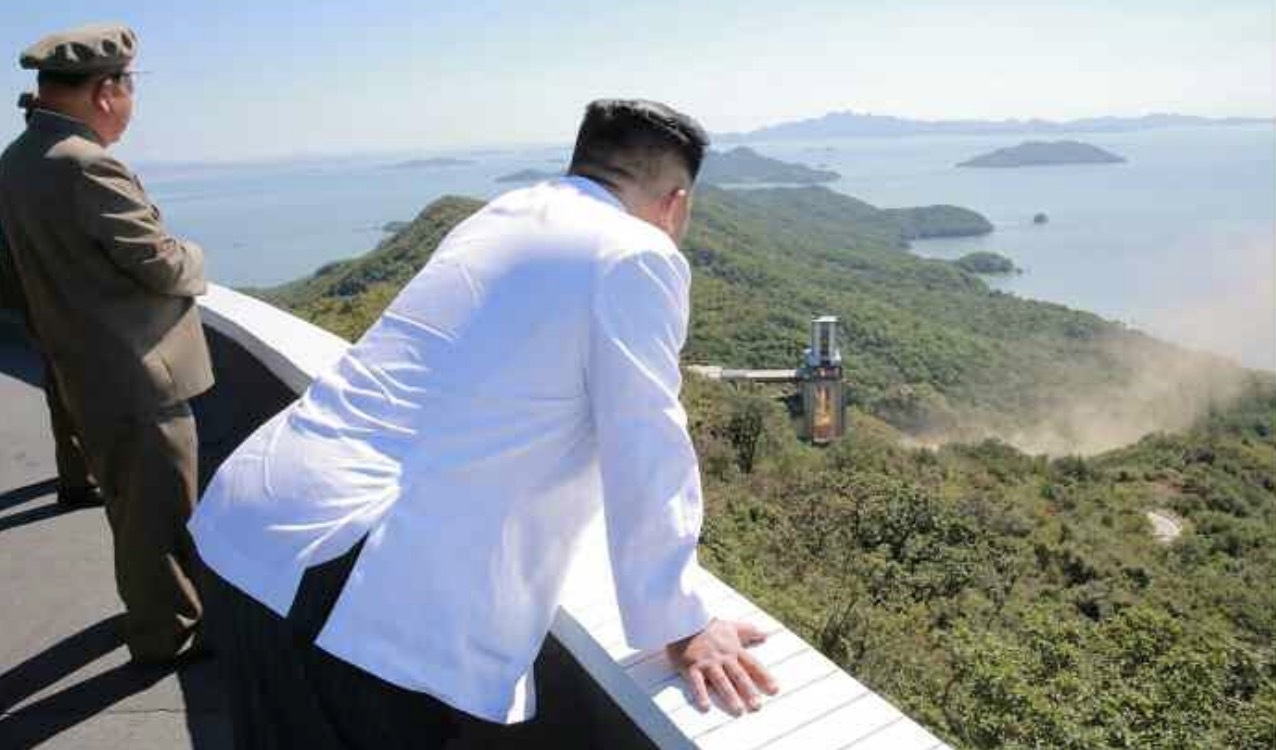

Analysis Failure to launch: Why North Korea’s satellite ambitions keep going up in flamesThird failure in four tries underscores systematic problems in DPRK space program despite Russian help, experts say  North Korea’s dream of building a network of satellites to spy on its enemies suffered a setback on Monday when its newest probe went up in flames, only six months after it successfully placed a military reconnaissance satellite in orbit for the first time. Experts told NK Pro that the failure underscores systematic problems in the cash-strapped regime’s space program that call into question the feasibility of Pyongyang’s satellite ambitions — as well as the impact of suspected Russian assistance. With three failures in four attempted launches over the past year, the apparent explosion of the new space launch vehicle should not come as a surprise, according to Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Noting that the failure happened in the first of the launch’s three stages, an issue that did not arise in the three other attempts over the past year, he said this showcases a “lack of technical maturity in the North Korean program.” “Presumably this failure could have happened on the previous launches and they were just lucky, and likely there is no aspect of the system which is robust in the sense that you can be confident that it’ll work this time even if it worked last time,” he told NK Pro. State media has not revealed much about the factors behind the failure of the late-night launch, with its claims of a new rocket model raising more questions than answers. The new space launch vehicle’s reported use of a “liquid oxygen and oil” combo suggests Pyongyang is continuing to experiment with its space technology rather than sticking to its previous formula, a conclusion supported by the fact that North Korea conducted more engine tests in advance of the launch. The apparent changes also hint at an outside hand in the development of the new rocket and satellite, adding to the case that Russia may be helping the isolated state advance its space program. In the long run, this support could play a big role in helping the DPRK overcome the limitations of a space program that has achieved little over the years, but for now, North Korea’s engineers will have to scramble to figure out what went wrong if they hope to make good on Kim Jong Un’s plans to place three more satellites in orbit this year. A video from South Korea’s JCS showing the rocket exploding in mid-air | Video: JCS (May 28, 2024) WHAT WENT WRONG North Korea made its fourth attempt at putting a military reconnaissance satellite on the first day of its weeklong launch window. But not long after the rocket blasted off from Sohae Satellite Launching Station, videos captured by Japanese media and the South Korean military showed it tilting upwards before exploding in a ball of fire off the Chinese coast. South Korea’s military subsequently reported that it detected “multiple fragments” over North Korean waters, but did not provide further details as it was still analyzing the apparent failure in coordination with the U.S. Shortly after midnight, North Korea’s externally focused Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) confirmed the failure of “the new-type satellite carrier rocket” carrying its “Malligyong-1-1” satellite. The vice director general of the National Aerospace Technology Administration stated that the rocket failed in mid-air during the first stage of its flight due to issues with the operational reliability of “the newly developed liquid oxygen and oil engine,” adding that experts will also examine other possible causes. State media did not elaborate on the new rocket’s fuel or how it differs from the Chollima-1 rocket that successfully placed a satellite in orbit in November, but the emphasis on developing a new type of engine could explain why it took six months for North Korea to attempt another launch after achieving success last November, according to Shin Seung-ki, a senior researcher at the Korea Institute of Defense Analyses (KIDA). “Technically, applying a new propellant requires significant time for testing to verify and enhance performance, reliability and stability,” he told NK Pro, adding that additional factors such as weather may have necessitated a longer wait. The name of the new satellite also hints at an incremental evolution from its predecessor, “Malligyong-1,” but state media did not report any details outlining possible changes to the probe.  CHANGING THE SYSTEM Having tasted success in November, North Korea’s switch to a different fuel combination begs the question: Why change a winning formula? Shin said the push to experiment may be part of a long-term vision to launch different kinds of military and commercial satellites in the future. “The Chollima-1 can place ultra-small satellites into low Earth orbit,” he explained. “Therefore, to launch larger and heavier satellites into orbit, they will need to develop launch vehicles and propulsion systems with improved thrust and efficiency.” McDowell said North Korea’s description of the new engine as using “oil” likely suggests a switch to a kerosene-liquid oxygen combination rather than dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) and unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH). He stated the Hwasong-15 ballistic missile, which is similar to Chollima-1 rocket, likely uses the latter combination as the fuel can be stored for years. But the kerosene-liquid oxygen combination is more suitable for space launch vehicles as it yields more energy and is less toxic, he added. However, he stated that this would require an entirely new engine, which would take a lot of time to develop. Hong Min, an analyst at the Korea Institute for National Analysis (KINU), agreed in a post-launch analysis that the new launch vehicle represents a switch from a hydrazine engine to a “safer” kerosene-based engine. Noting that Russia favors a kerosene-based propellant, he suggested Pyongyang could have switched to the new system to align its space technologies more closely with its ally as part of efforts to boost space cooperation. “This transition likely involved consultation or support from Russian experts, considering the current global trend and North Korea’s use of Russian expertise,” he stated. Young-keun Chang, a director at the Korea Research Institute for National Security (KRINS), also emphasized the possibility of Russian involvement and suggested North Korea would need assistance with developing technologies capable of maintaining liquid oxygen at temperatures as low as -183 degrees Celsius. “Developing a rocket for cryogenic propellants would take at least two to three years,” he told NK Pro. “It is more likely that North Korea acquired this engine from Russia as part of a cooperation agreement and conducted several ground combustion tests before launching it, rather than developing the engine in a short period.” He added that Moscow likely supplied the RD-151 engine, which South Korea also uses in its Naro-1 rocket.  PYONGYANG’S NEXT STEPS The failed launch represents a significant setback for North Korea’s space program, but experts said it can still continue working toward its goals by addressing current flaws and bolstering its capabilities with outside support. “The ‘failure’ of a satellite launch is common among space-developing countries, and North Korea quickly acknowledged and reported the failure,” KINU’s Hong said. However, he added that North Korean scientists will need at least three to six months to fix the problems with the new engine, which would make it difficult to achieve Kim Jong Un’s stated aim of carrying out three launches this year. KIDA’s Shin also identified a similar time frame for fixing the first-stage engine’s issues and added that monsoons and typhoons in the summer will also prevent launches in the next few months. “If a re-launch is successful as early as possible after September, consecutive launches are not impossible. However, if the re-launch also fails, it will be practically impossible to launch three satellites within this year.” To ensure success, he said North Korea will need to identify the cause of the explosion, improve the rocket’s design, materials, and components and conduct additional ground tests to ensure stability and reliability. Outside technical support could help overcome these challenges, and Hong suggested Russia could look to increase its influence ahead of Vladimir Putin’s anticipated visit to North Korea. “The recent failure is unlikely to affect North Korea-Russia relations adversely,” he said. “Instead, it might prompt more proactive technical assistance to improve success rates and stability.” Shin suggested North Korea could even consider using Russian rockets to launch multiple satellites in the future, but that this cooperation is unlikely to extend to more high-profile initiatives. “Taking into account the prestige of North Korea’s Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un, it is thought that using Russian launch vehicles for North Korean-developed satellites would be difficult for the time being,” he stated. “Doing so would undermine the meaning, value and purpose of ICBMs and satellite launch vehicles like the Chollima-1, developed at great cost, time and the sacrifices of the North Korean people.” Anton Sokolin and Joon Ha Park contributed reporting to this article. Edited by Bryan Betts © Korea Risk Group. All rights reserved. |

The ultimate resources for professionals working on North Korea